The Monstrous Flora of Romeria

Romeria is a world where the trees are not passive background decoration. They are active participants. Some of them feed you. Some of them trap you. Some of them stare at you until you regret most of your childhood. And a few of them simply poison the air and wait.

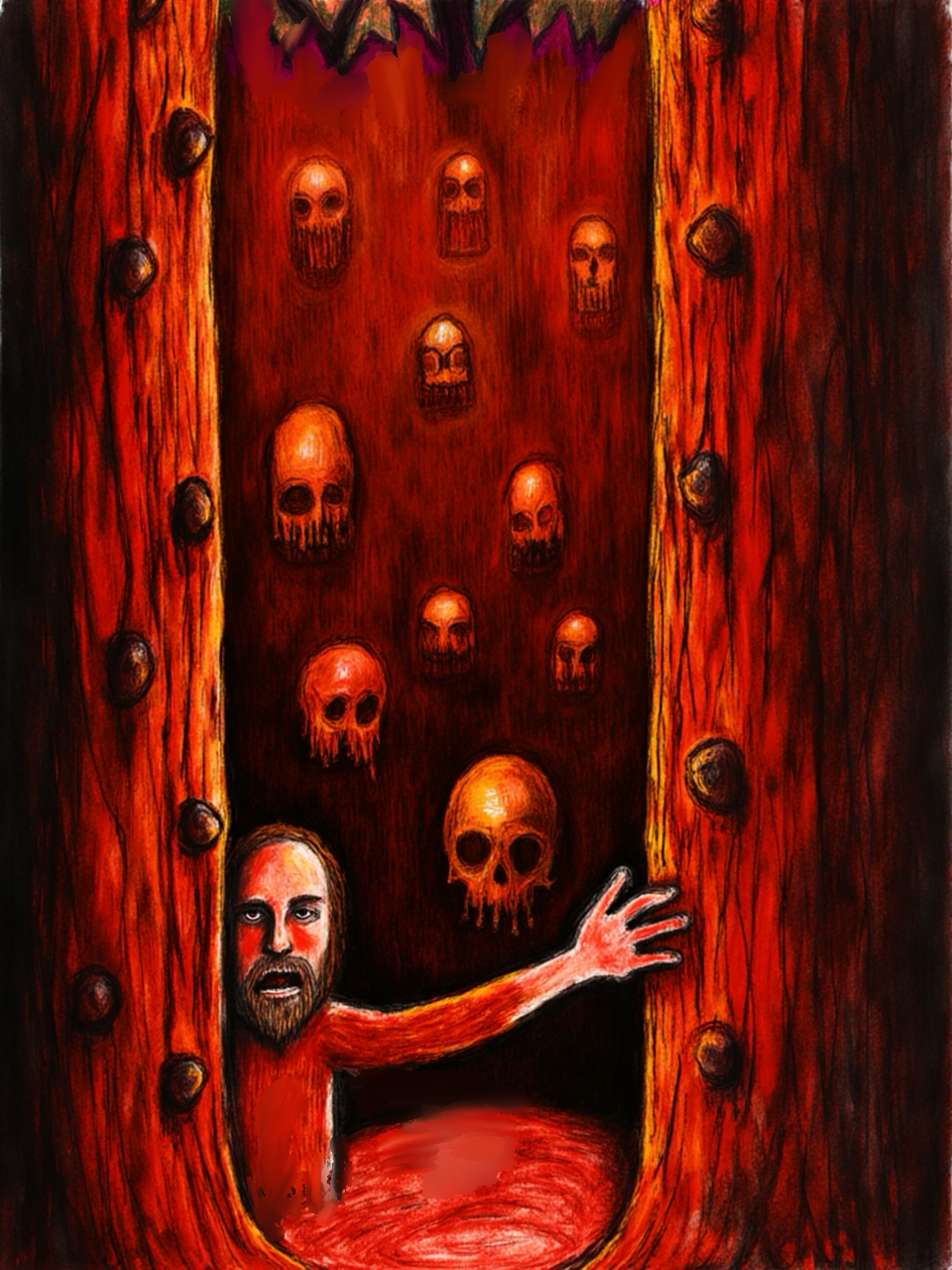

The first tree I created was the sap-feeding tree — a tall, luminous thing with a permanent vertical mouth running through its trunk. Inside is a glowing pink-red substance, somewhere between Turkish delight and biological mistake. It smells sweet, looks edible, and tastes comforting enough to make people linger. The tree feeds them gently, indulgently, like it’s being kind. Then, once they’re calm and distracted, it closes. The spikes were visible the whole time. Nobody complains. They were busy eating.

The second tree is quieter and more deceptive. Its leaves glow softly, hypnotically, catching the eye from a distance. People don’t realise they’re being drawn in — they just feel compelled to walk closer, to stand beneath it, to admire the colour. The ground looks solid. It isn’t. Beneath the surface is a liquid chamber lined with organic spikes. Once someone breaks through, they sink slowly, watching the beautiful leaves above them while disappearing into something much less poetic.

Then there are the sticky-leaf forests. These are some of my favourites because they feel almost petty. The leaves cling. They accumulate. They don’t attack so much as refuse to let go. People get stuck, gradually buried, hallucinating as fungal spores drift through the air. It’s not dramatic. It’s administrative. The forest simply files you away.

The Eye Tree comes next — a living trunk with a single enormous eye. It doesn’t kill you outright. It won’t even let you leave. It just watches. People freeze beneath its gaze, suspended, unable to move on until they speak. Confessions surface. Things they didn’t intend to say. Things they refuse to admit. And if they refuse — if pride or ego keeps their mouth shut — the tree keeps them there. Motionless. Waiting. Eventually, the silence does the work.

Further in, there’s the plant that looks like a cave but absolutely isn’t. A fleshy red structure with multiple chambers, like two swollen stomachs stitched together. One end opens into a wide orifice that releases thick yellow gas — so foul it stops being funny and becomes neurological. People stagger, gag, collapse. The plant digests slowly and fertilises the ground afterward. Very efficient. Very smug.

And towering above everything else are the megatrees — colossal organisms miles high, visible across entire basins. Whole civilisations live inside them, burrowed into bark and root, descending by ropes, gliding out in wingsuits, defending their home with arrows and water systems grown directly into the tree itself. These trees don’t hunt. They don’t lure. They don’t need to. They already won by existing.

What I’ve come to really like about illustrating these plants is how uncanny and imperfect the images are. They aren’t slick or polished. They feel childlike in a way that contradicts the subject matter — awkward proportions, strange anatomy, expressions that don’t quite match the horror. And that contradiction is exactly what makes it work.

Romeria is dark, but I don’t want it to be heavy in a joyless way. By leaning into absurdity, deadpan humour, and a slightly naïve visual language, the darkness becomes strange instead of oppressive. Laughable, even. A man politely eating glowing tree jelly or waving as he’s poisoned by a farting plant feels more honest than endless seriousness.

These trees aren’t meant to impress.

They’re meant to exist.

And Romeria is full of them.